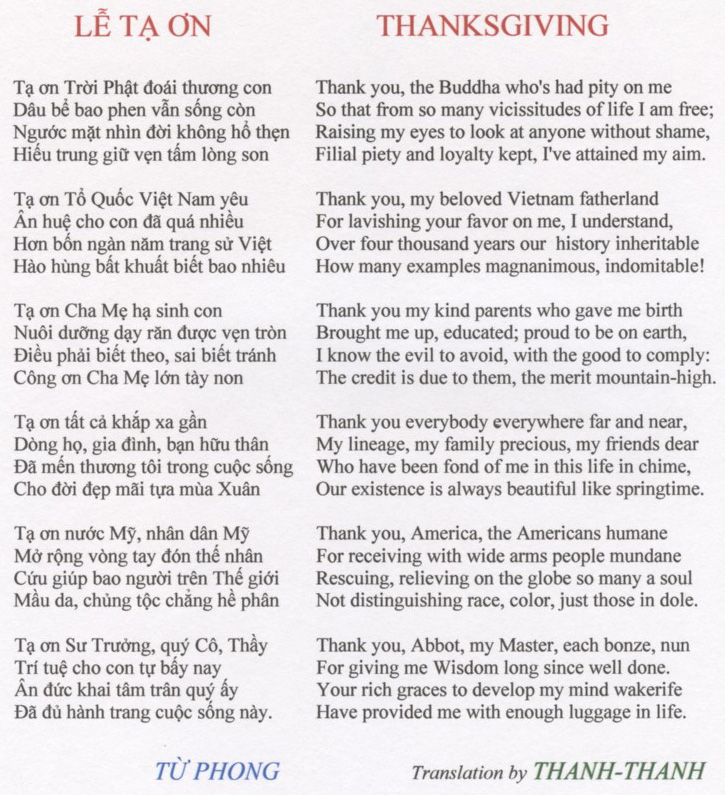

Thanksgiving – Lễ Tạ Ơn

Thơ Song Linh

Thanh Thanh chuyển dịch

NGÀY THÁNG TÁM

Ngày tháng tám mùa thu về rất lạ

Em mắt buồn theo cỏ lá heo may

Đường thở dài vàng nắng áng mây bay

Tình cúi mặt để sầu rêu nhánh lá

Ngày tháng tám mùa thu xanh biển cả

Cánh chim về hong ấm nụ môi hôn

Bài thơ yêu nhung nhớ lại gần hơn

Căn gác nhỏ mở lòng vui đất lạnh

Ngày tháng tám mùa thu vàng đất trắng

Tay em mềm gối mộng ngát trùng dương

Con sóng vỗ thềm trăng mòn vách đá

Gió thu về mây trắng đẹp trời hương

Ngày tháng tám mùa thu trùng xuống thấp

Đất khóc thầm tan vỡ mối tình hoa

Em nói dối ta buồn như muốn khóc

Con thuyền nào chở hết cõi lòng ta

Ngày tháng tám mùa thu về thêm tuổi

Đất mẹ nghèo mọc cánh vỗ trời hoang

Và tình ta từ đó cũng lang thang

Khi trước mặt cuộc đởi chưa đáp số

SONG LINH

A DAY IN AUGUST

That day in August, Autumn seemed so strange;

Your eyes grew sad like in grass blades a change.

The road sighed in the yellow cloudy sun,

Love faced down, anxiety got leaves moss dun.

Also a day in August, Autumn had been sea blue;

The birds had returned to warm their kiss due;

The romantic poem of each other helping take hold;

The small attic opening its heart on the land tho cold.

On that day in August, Fall had gilded the white earth;

Your soft arms as dreamy pillows in an ocean mirth;

Crashed by the waves in the moon the cliff worn;

The fall wind bringing back a clear perfumed morn.

Then, that day in August, Autumn sank abruptly low,

The ground silently cried, broken the love glow.

You lied to me so that I felt I wanted to weep,

No vessel could transport my soul in sorrow deep.

Yes, that day in August returned adding a year in age,

My poor maternal place grew wings to a wild stage;

And my love too since then got adrift dilution

While my immediate existence had not yet a solution.

Translation by THANH-THANH

THÚY ĐINH

In The Mountains Sing, Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai has created a luminous, complex family narrative that spans nearly a century of Vietnamese history, from the French colonial period through the communist Viet Minh’s rise to power, the separation between North and South Vietnam, the Vietnam War, all the way to the present day. Told alternately by Diệu Lan, born in 1920, and her granddaughter Hương, born in 1960, the novel resembles a choral performance with multiple voices.

Diệu Lan is the family matriarch — bereft of father, husband, brother, and eldest son due to war and occupation, she weathers historical changes and economic hardship with self-reliance, intelligence, creativity, and kindness. Born in the same province as revolutionary leader Hồ Chí Minh, Diệu Lan’s actions reflect her own idea of independence. During the era before Vietnam’s economic reforms of the 1980s, she becomes a black marketeer to improve her family and community living conditions. She introduces contraband American literature to her granddaughter, hoping to broaden Hương’s intellectual horizons, and shows unwavering love to a son who fought in the pro-American South Vietnamese Army.

The Mountains in the title represent the Vietnamese people and their land, and Sing standsfor the novel’s celebration of plural perspectives. Mountains Sing is also the literal meaning of sơn ca, the Sino-Vietnamese word for the hand-carved wooden lark that Hương inherits from her long-lost father. As a symbol of immortality in Vietnamese culture, the sơn ca also brings to mind Yeats’s golden nightingale, his avatar in “Sailing to Byzantium” that sings of “what is past, or passing, or to come.”

The past figures prominently in Quế Mai’s novel, for it still affects the present and the future. The author dedicates The Mountains Sing to her grandmother, who perished in the Great Famine of the 1940s when Japan occupied Vietnam, to her grandfather who died because of the harsh land reform policy imposed by the North Vietnamese Communist government in 1955, and to her uncle, “whose youth the Vietnam War consumed,” as well as millions of Vietnamese and non-Vietnamese who lost their lives in the war.Article continues after sponsor messagehttps://5bacdb423a428db7f08f7e251c8d88b2.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-37/html/container.html

‘The Mountains Sing’ affirms the individual’s right to think, read, and act according to a code of intuitive civility, borne out of Vietnam’s fertile and compassionate cultural heritage.

Born in 1973 in North Vietnam, Quế Mai relocated at six with her family to the South, before winning a university scholarship to study in Australia. She later decided to pursue a writing career exploring the long lasting socio-psychological consequences of the Vietnam War. This background gives Quế Mai an astute and graceful ability to sustain contradictory truths about war, displacement, aesthetic representations, and human nature. In The Mountains Sing, Hương is able to see the humanity of her so-called American enemies because she’s read Laura Ingalls Wilder’s depiction of the close-knit pioneer family in Little House in the Big Woods (a book she acquired from her grandmother Diệu Lan’s black market trade). At the same time, beauty does not exempt a culture from its inhumanity; at one point, Diệu Lan observes that an elegant haiku about a frog by the Japanese poet Basho could not save the Vietnamese from the brutality of their Japanese occupiers.

Most importantly, the novel helps all of us see “the enemy” not as abstract or demonic, but corporeal, even familial. An American bomber who falls out of the sky, Icarus-like, is as vulnerable as someone’s brother who fights for the other side. The Vietnam War is not only an international ideological struggle, but also a civil war among kin. A character laments, “But what if one of my comrades had his gun pointed at your forehead? Would I kill my brother in arms to save my brother in blood?”

In depicting the dire consequences of war and Marxist ideology, which forced citizens and family members to become either traitors or patriots, The Mountains Sing affirms the individual’s right to think, read, and act according to a code of intuitive civility, born out of Vietnam’s fertile and compassionate cultural heritage.

And yet, despite the novel’s wondrously balanced approach, true reparation has yet to take place between the Vietnamese state and its people. The “enemies” that Diệu Lan faces when she returns to her home town are not her true enemies, but merely agents of an oppressive Marxist regime that engineered the disastrous land reform.

At the end of the day, the fact that The Mountains Sing is published in English means its content still faces translation and censorship hurdles before reaching readers in Vietnam. Can Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai’s message be heard in her homeland, where the mountains of Vietnam are still a fortress silencing the sounds of birds?

Thúy Đinhis a writer, literary translator, and co-editor of the Vietnamese e-zine Da Màu (Multitude). Her work has appeared in NBCThink, Asymptote, diaCRITICs, Amerasia Journal, Pop Culture Nerd, among others.

A team from the Archaeological Survey of India have announced the discovery of a monolithic sandstone Shiva Linga dating from around the 9th century AD in the Quảng Nam province, Vietnam.

The Archaeological Survey of India is an Indian government agency attached to the Ministry of Culture that is responsible for archaeological research and the conservation and preservation of cultural monuments.

The discovery was made during a conservation project at Mỹ Sơn, an archaeological site consisting of Hindu temples constructed between the 4th and the 14th century AD by the Kings of Champa, an Indianised kingdom of the Cham people.

The Mỹ Sơn temple complex is regarded as one of the foremost Hindu temple complexes in Southeast Asia and is recognised as a UNESCO world heritage site.

The linga, also called a lingam is an abstract or aniconic personification of Shiva in Shaivism and is generally the primary murti image in a Hindu temple dedicated to Shiva. Lingam iconography is often found at archaeological sites of the Indian subcontinent and southeast Asia that includes simple cylinders set inside a yoni.

The External Affairs Minister for India, S. Jaishankar said: “A great cultural example of India’s development partnership.”

Anh đứng đây trông về nơi em

qua một phía trời có mây và nắng

nắng trải rất mềm hàng cây đứng lặng

mây xõa lưng chừng anh ngẩn ngơ thêm

Anh đứng đây trông về nơi em

qua những lớp dày kẽm gai tường đá

có những cảnh đời rất quen mà lạ

lập lại từng ngày sáng tối chiều trưa

Anh đứng nơi đây trông về phố xưa

cách một quãng đường vài trăm cây số

kỷ niệm ngày nào rất nhiều để nhớ

như nhớ thương em nhớ mấy cho vừa

Anh đứng hôm nay trông về hôm qua

vượt mấy thời gian xô về dĩ vãng

có một rừng thơ một trời sao sáng

em đưa xuân về mấy độ hương hoa

Anh đứng hôm nay trông về hôm qua

non nước lênh đênh phận người dâu bể

thương quá từng đêm phòng khuê đơn lẻ

xin hẹn nhau ngày tàn cuộc phong ba

Anh đứng hôm nay trông về ngày mai

mộng ước mai sau mộng ước thật dài

hạnh phúc, quê hương, tình yêu, cuộc sống

còn đấy rất nhiều dự tính tương lai.

SONG NHỊ

I stand here

and look at your residing place

Through a full-of-clouds-and-sunshine space.

Quiet are lines of trees and mild the sun spread;

Half-way clouds hang down and more moved I get.

I stand here and gaze

upon the zone you abide

Over barbed wires and stony walls that divide.

Quite a lot of life sights very familiar but unusual

Occur every morning and evening repeatedly dual.

I stand here and observe

our dear former abode

Some hundreds of kilometers hence apart a road.

Memories of those days are numerous to treasure

And countless to miss and love you to my pleasure.

I stand here today to

look back on the ancient times

Reaching to bygone dates, rushing to old climes.

A universe of muse, a sky of starlight you did bring

Perfumes and flowers manifold the spirit of spring.

I stand here today to

think of the past and hate

The vicissitudes as our country and people’s fate.

What a pity lonely you are spending every night!

I promise to reunite with you when ends this plight.

I stand here today to

look forward to tomorrow

Nurturing dreams about our future free from sorrow.

There are our Happiness, Motherland, Love, Life,

And for hereafter so many plans, so much to strive.

Translation

by THANH-THANH

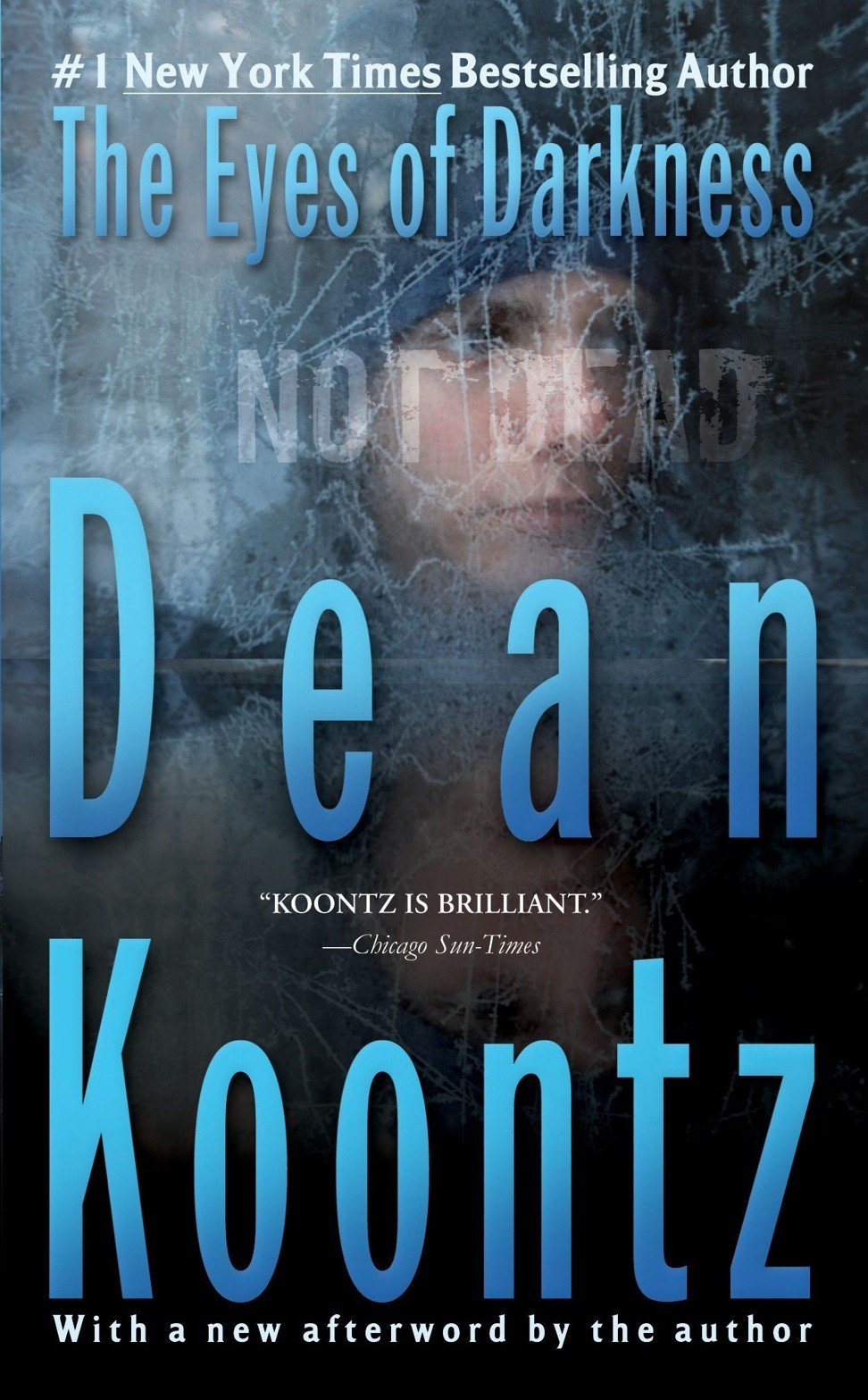

Kate Whitehead

The Eyes of Darkness,

a 1981 thriller by bestselling suspense author Dean Koontz, tells of a

Chinese military lab that creates a virus as part of its biological

weapons programme. The lab is located in Wuhan, which lends the virus

its name, Wuhan-400. A chilling literary coincidence or a case of writer

as unwitting prophet?

In The Eyes of Darkness,

a grieving mother, Christina Evans, sets out to discover whether her

son Danny died on a camping trip or if – as suspicious messages suggest –

he is still alive. She eventually tracks him down to a military

facility where he is being held after being accidentally contaminated

with man-made microorganisms created at the research centre in Wuhan.

If

that made the hair on the back of your neck stand up, read this passage

from the book: “It was around that time that a Chinese scientist named

Li Chen moved to the United States while carrying a floppy disk of data

from China’s most important and dangerous new biological weapon of the

past decade. They call it Wuhan-400 because it was developed in their

RDNA laboratory just outside the city of Wuhan.”In

another strange coincidence, the Wuhan Institute of Virology, which

houses China’s only level four biosafety laboratory, the highest-level

classification of labs that study the deadliest viruses, is just 32km

from the epicentre of the current coronavirus outbreak. The opening of the maximum-security lab was covered in a 2017 story in the journal Nature, which warned of safety risks in a culture where hierarchy trumps an open culture.

Koontz has written more than 80 novels and 74 works of short fiction. Photo: Douglas Sonders

Fringe

conspiracy theories that the coronavirus involved in the current

outbreak appears to be man-made and likely escaped from the Wuhan

virology lab have been circulated, but have been widely debunked. In

fact the lab was one of the first to sequence the coronavirus.

In

Koontz’s thriller, the virus is considered the “perfect weapon” because

it only affects humans and, since it cannot survive outside the human

body for longer than a minute, it does not demand expensive

decontamination once a population is wiped out, allowing the victors to

roll in and claim a conquered territory.

It’s no exaggeration to call Koontz a prolific writer. His first book, Star Quest,

was published in 1968 and he has been churning out suspense fiction at a

phenomenal rate since with more than 80 novels and 74 works of short

fiction under his belt. The 74-year-old, a devout Catholic, lives in

California with his wife. But what are the odds of him so closely

predicting the future?Post Magazine NewsletterGet updates direct to your inboxBy registering, you agree to our T&C and Privacy Policy

Albert

Wan, who runs the Bleak House Books store in San Po Kong, says Wuhan

has historically been the site of numerous scientific research

facilities, including ones dealing with microbiology and virology.

“Smart, savvy writers like Koontz would have known all this and used

this bit of factual information to craft a story that is both convincing

and unsettling. Hence the Wuhan-400,” says Wan.

British

writer Paul French, who specialises in books about China, says many of

the elements around viruses in China relate back to the second world

war, which may have been a factor in Koontz’s thinking.

“The

Japanese definitely did do chemical weapons research in China, which we

mostly associate with Unit 731 in Harbin and northern China. But they

also stored chemical weapons in Wuhan – which Japan admitted,” says

French.

Publisher

Pete Spurrier, who runs Hong Kong publishing house Blacksmith Books,

muses that for a fiction writer mapping out a thriller about a virus

outbreak set in China, Wuhan is a good choice.

“It’s

on the Yangtze River that goes east-west; it’s on the high-speed rail

that goes north-south; it’s right at the crossroads of transport

networks in the centre of the country. Where better to start a fictional

epidemic, or indeed a real one?” says Spurrier. (Spurrier works

part-time as a subeditor for the Post.)

Hong Kong crime author Chan Ho-kei believes that this kind of “fiction-prophecy” is not uncommon.

“If

you look really hard, I bet you can spot prophecies for almost all

events. It makes me think about the ‘infinite monkey’ theorem,” he says,

referring to the theory that a monkey hitting keys at random on a

typewriter keyboard for an infinite amount of time will almost surely

type any given text.

“The probability is low, but not impossible.”

Chan points to the 1898 novella Futility,

which told the story of a huge ocean liner that sank in the North

Atlantic after striking an iceberg. Many uncanny similarities were noted

between the fictional ship – called Titan – and the real-life passenger

ship RMS Titanic, which sank 14 years later. Following the sinking of

the Titanic, the book was reissued with some changes, particularly in

the ship’s gross tonnage.

“Fiction

writers always try to imagine what the reality would be, so it’s very

likely to write something like a prediction. Of course, it’s bizarre

when the details collide, but I think it’s just a matter of

mathematics,” says Chan.

Many of Koontz’s books have been adapted for television or the big screen, but The Eyes of Darkness

never achieved such glory. This bizarre coincidence will thrust it into

the spotlight and may see sales of this otherwise forgotten thriller

jump.

Amazon is currently offering it on Kindle for just US$1. Perhaps, like Futility, it will also be reissued with some updates to make it really echo the current outbreak.

Source Internet

By SCU

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen review – a bold, artful debut

The book won the Pulitzer, and in 2017 Nguyen was awarded a MacArthur “genius” grant and published a collection of stories, The Refugees. The distinction between immigrant and refugee was a central part of Nguyen’s talk and reading on campus last fall.

“We hated immigrants before, some of us hate immigrants now, but the point is that immigrants are part of the American mythology,” Nguyen said. “They’re part of the American dream. Immigrants validate the United States, whether or not we want them to come here at all. Refugees are completely different. Refugees are the unwashed, they are the unwanted, they come bringing with them the stigma of all kinds of fears of contamination, the idea that they come from broken states and broken countries.”

Nguyen himself is a refugee. He was born in the central highlands of Vietnam, and after the fall of Saigon in 1975, his family fled to the United States. He grew up in San Jose and witnessed his vibrant Vietnamese community “still suffering traumatically from what had happened to them,” as he put it. “I grew up hearing all these stories about what the Vietnamese people had gone through. And, at the same time, I was growing up as an American. And I was getting a very different version of this war from American culture.”

Case in point: the jarring difference between the treatment that a film like Apocalypse Now dealt Vietnamese people, versus how Vietnamese people saw themselves. With The Sympathizer, Nguyen set out to try to undo a sense of victimization.

His novel is a tale of America as well as Vietnam. “We were lucky as refugees to come to this country,” he said. “We were not special. And people who were refugees need to stand up for people who are refugees today. Which is why I always claim I’m still a refugee.”

His willingness to tackle difficult subjects has led to him being called a “voice for the voiceless”—a moniker with which he takes umbrage. “The problem, of course, is not that the Vietnamese people are voiceless,” he said. “It’s that no one wants to hear them … Any type of minority—we’re up against systems and structures who don’t want to hear from us, who don’t actually want to give voices to the voiceless. They just want representatives to make it easier for us to be heard. That’s the role I resist.”

Nguyen spoke to a packed house at the de Saisset Museum on October 19. His visit was part of the Reading Forward series, co-sponsored by the Santa Clara Review, the Creative Writing Program, and the Department of English. The series brings writers to campus to participate in classes as well as meet with students and faculty in small groups to discuss writing and publishing. On that front: Nguyen is currently working on a sequel to The Sympathizer called The Committed.